New Projects

Information, Civil Society and Corruption in Guatemala

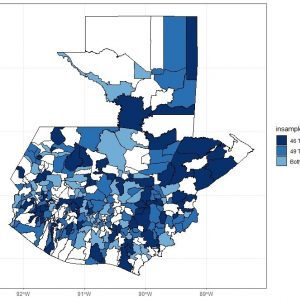

In the past 10 years, corruption scandals, particularly those related to public procurement, have caused the removal of presidents in Brazil, Guatemala and Perú. Ongoing corruption scandals continue to rattle civic space across many countries. Considerable programming and research has focused on disseminating information about government malfeasance with an eye toward promoting transparency. The efficacy of such information likely varies depending on the way in which it is delivered. We propose to examine alternative ways to disseminate information on government malfeasance in public procurement in Guatemala’s municipalities. In particular we ask: Is it more effective to provide information on past corruption to citizens themselves or the bureaucrats who are directly engaged in procurement? To answer this question, we have partnered with the Guatemalan think tank ASIES to develop two different information interventions directed to local civil society and municipal bureaucrats, respectively.

The project is composed of an intervention with two treatment arms, two sets of surveys, and web scraping of administrative data from municipal procurement contracts. The two treatment arms will be composed of two different kinds of informational videos, tailored to local civil society leaders and municipal bureaucrats with experience in public procurement.

Fake Media, Corruption and Democratic Backsliding in El Salvador (with Erik Wibbels and Ernesto Calvo).

Nayib Bukele came to power in 2019, presenting himself as a political outsider –despite having been elected mayor with FMLN before temporarily switching to GANA for the 2019 presidential elections— promising to fight corruption and to implement an ambitious infrastructure plan. While many important infrastructure projects have been completed since Bukele came to power, he has captured the institutions of justice, harassed the press and even attempted a coup on February 9th, 2020. In the independent media, there are many reports of corruption in the government’s infrastructure projects, but contrary to his campaign promises Bukele has rejected attempts to set up an independent body to investigate and prosecute corruption. Indeed, Bukele broke his 2019 agreement with the Organization of American States to set up a commission—CICIES—tasked with helping local prosecutors investigate corruption cases once those prosecutors began targeting members of his government. Instead of prosecuting corruption, Bukele has gone after journalists for their coverage of corruption scandals in effort to silence their work. His government has started investigations against elFaro for alleged money laundering, and he regularly criticizes established print newspapers (El Diario de Hoy and La Prensa Gráfica) as well as digital outlets (Revista Factum and Gato Encerrado).

A key feature of the success of Bukele’s “Millennial Authoritarianism” (Meléndez-Sánchez, 2020) is his manipulation of the media environment through the effective use of social media to both promote his image and spread positive, fake news. Bukele’s own popularity started on TikTok, and his campaign relied heavily on social media to promote his image. Once in power, Bukele has continued to rely on social media to control the information environment in two different ways: First, through the use of bots and fake accounts to combat criticism in social media;1 and second, through the dissemination of fake news from newly created newspapers such as the official Diario El Salvador through social media platforms, particularly Facebook and Twitter.2

In this project, we explore whether and how these social media-based strategies work, i.e. if, when and how they crowd out serious reporting on corruption in El Salvador. In order to accomplish this, we will scrape articles from propaganda outlets and compare their content to that of traditional outlets; we will focus specifically on corruption, but we will also compare how the two types of media cover the full range of civic space, including the 18 civic space event types the Machine Learning for Peace project is already collecting data on. First, we will focus on content and relative coverage, i.e. whether a given outlet publishes articles about government corruption and the share of its daily, weekly and monthly coverage devoted to those stories. To study whether articles published by propaganda outlets actually crowd out the information environment, however, we proposed to rely on data from Facebook and Twitter. We will measure the number of times articles are shared/read to assess the degree to which: (a) propaganda travels across information networks—one important output of the project will be to map the social media network surrounding the president and his supporters; and (b) propaganda actually crowds out real news. Second, we will study Twitter activity –given the fact that Bukele himself is a big user— to see whether fake news and content generated by propaganda outlets is deployed by Bukele-aligned Twitter accounts around corruption scandals as one more tool to change the narrative. To accomplish this, we have partnered with a group of journalists from Revista Gato Encerrado, an online investigative journalism outlet from El Salvador.